Dive Adventure: Diving the Arctic

Dive Adventure: Braving the Arctic

Scuba diving and underwater photography near the North Pole

By Kevin Lee

“Diving in Arctic waters will be warmer than when we dived in the Antarctic," my buddy said, “because the warm Atlantic Gulf Stream current travels far north and warms the polar region." That prospect sounded inviting so I signed up for the adventure. True enough, it was warmer diving in the Arctic, but only by 2 degrees, as my dive computer registered 30 degrees in Svalbard, Norway, an archipelago of islands far above the Arctic Circle, about 600 miles from the North Pole.

Perry, Kevin Lee, Jeff Bozanic, and John Lee. Photo courtesy of Debbie Smerker.

Scuba tanks, filled and ready for use. All tanks had two independent primary valves for separate regulators. Insurance in case one uncontrollably free-flowed.

Diving and underwater photography in the Arctic

In six days, I completed 8 dives. Water temps varied from 29 to 41 degrees and visibility ranged anywhere from 5 feet to 50 feet. As in the Antarctic, dive duration was limited, not by the amount of air in our 80cf steel tanks, but by our capacity to endure increasing pain, from the frigid waters, which first accost the hands and then the feet. My longest dive was 61 minutes. A few brave souls utilized wet gloves and were usually the first out of the water. Some, with dry gloves, experienced leaks and had to call their dive within minutes. Having dived both Polar regions, I must applaud the Dive Concepts and similar dry glove systems. Knock on wood, of course, but these dry gloves have not failed a single time in hundreds of dives. They are so easy to snap on and off, I cannot see why others struggle with other less functional glove systems that continually fail and produce great frustration.

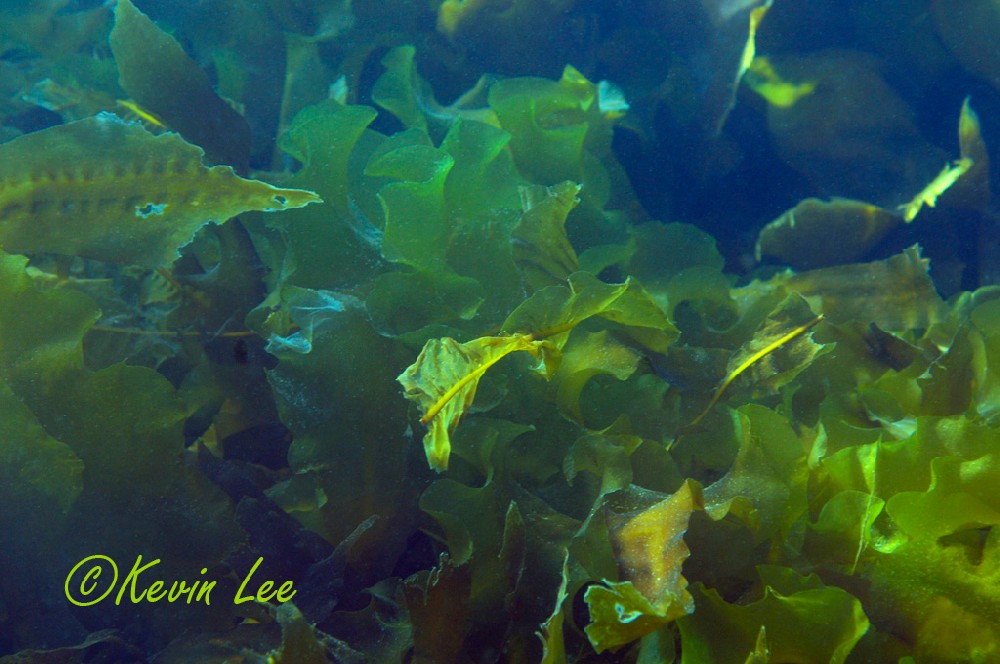

Dense undergrowth of kelp was common at most dive sites.

At most dive sites, there was a surprising thicket of kelp, among which flourished amphipods, stars, snails, tunicates, anemones, crabs and other crustaceans and a few fish, the largest a dark sculpin-like fish at 8 inches long. We did one bottomless, open-water dive at the edge of an ice sheet, where buoyancy was difficult to control due to the constant mixing of fresh and salt waters of differing densities. Here, ctenophores were plentiful, many like the Beroe which resemble inverts back home in California. Of particular interest was the pelagic opisthobranch, yes, a sea slug, Clione limacine, that lives in the water column. Its common name, Sea Angel, is apt as it has two wing like appendages that makes it appear to “fly."

Clione limacina, aka Sea Angel, approx. 1.5 inches.

Limacina helicina, aka Sea Butterfly, approx. 3/4 inch. This is the prey of the Sea Angel, which is pictured above.

Underwater photography tips

Kevin used a Nikon D300, with 60mm macro lens and 1.4x tele-converter which worked well for macro shots. Visibility was generally good enough for wide-angle underwater photography, though macro opportunities are more prevalent. A Sea & Sea housing was used, with dual YS-110a strobes. Some think camera gear should be kept outside to minimize condensation. This is not necessary and the author does not recommend this. The air is so arid condensation is not a problem, as long as there is good ventilation inside your room. After each dive, change batteries in both the camera and strobes, as batteries have significantly shorter lives in cold temperatures. Dry gloves are best, with medium inner gloves, providing enough dexterity to operate housing buttons.

Special diving tips for Arctic diving

Chiton.

Dendronotus sp. nudibranch

Sculpin-like fish. ID Unknown.

Benthic Jelly.

Arctic nudibranch, ID unknown.

Memorable adventure under the ice

One dive is most memorable as it was potentially the most dangerous. My buddy, Jeff Bozanic, and I were the last two divers blowing bubbles, as others had already surfaced. We were both engrossed in collecting echinoderms for the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History (we had the requisite Norwegian permits) and we were covered with a thick carpet of kelp, which lay horizontal from a constant, pesky current. Occasionally I would look up to see only Jeff’s long legs sticking out of the kelp, as his face was stuck underneath, poking around for critters. Sometimes we’d accidentally whack the other in the head with our fins, assuring each other that we were “together." At 500 psi, I decided to head for more shallow water and indicated my intention to Jeff, who gave me the "ok" sign. I followed the steep contour of the rocky slope up to 15 feet, all the while still searching for echinoderms and opisthobranchs.

Limacina helicina, aka Sea Butterfly.

Approx. 3/4 inch. Algae background. 10' fsw.

With my safety stop completed, I looked around and behind to find a suitable place to surface but was stunned to see a massive sheet of ice, 25 feet deep and extending as far as I could see both directions, moving toward me. My heart pounded against my rib cage. What to do? With my air reserve depleted at 200 psi it was not an inviting option to duck under the ice and risk running out of air, trying to swim out from under the huge ice floe. Also, I considered going down to Jeff and warning him of the threat but he was well under the oncoming ice and in a safe zone as long as he had sufficient air.

It would be perilous for me to stay in place as the monstrous ice would crush me like an ant against the vertical rocky wall. By this time, I decided to surface and could see Henrik, alone in our Zodiac, about 100 yards down current, frantically trying to push the ice away with the craft, though it made no impact whatsoever against the inertia of the football field sized ice sheet, inexorably approaching. If needed, I prepared to ditch all my gear and scramble on top of the oncoming ice, though this maneuver would be fraught with its own dangers. Pressed for a decision, I peered down in the water a final time to assess the situation and noticed that the base of the ice floe would soon contact an outcropping of rocks twenty feet at the bottom. It did with explosive power and sent large chunks of ice showering upward. This momentarily arrested the movement of the ice and gave me a tiny window of time to fin like hell and scramble onto the Zodiac, which zipped away just in time to avoid the crushing ice. Thankfully, Jeff appeared on the opposite, safe side of the ice floe and we picked him up.

It was certainly a dive to remember!

Wildlife

Wildlife was plentiful with frequent sightings of polar bears, walruses, foxes, seals, whales, and thousands of birds fluttering around breeding cliffs, swarming like bees around a hive. Oddly there, are no penguins in the Arctic and no polar bears in the Antarctic. Every zodiac is armed with flares and a rifle to warn, ward off and, if needed, subdue any menace from polar bears as Svalbard, Norway is home to the largest population in the world of these magnificent creatures. In one incident years ago, a diver was pursued by a polar bear, forcing the diver to descend to 60 feet, at which time the bear gave up the chase. Thankfully, we had no such traumatic encounter with the wild beasts.

Zodiacs and MV Plancius, our floating base camp.

Mother Polar Bear checking on her cubs.

Getting There

Using connecting flights through London and Oslo, I reached Svalbard’s largest town, Longyearbyen, home to about 2500 inhabitants, which is on Spitsbergen, the major island of the archipelago. Coincidentally, the town is named after an American, John Longyear, who was the main shareholder of a company that mined coal from 1905. Coal reserves are dwindling and tourism contributes much to the town’s economy. By the way, high on a hill, near the Longyearbyen Airport, one can see a drab concrete structure which appears to be some sort of an entrance. Indeed, this is the site of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, where millions of the world’s seeds are stored in permanent deep freeze as protection against natural and human disasters.

MV Plancius, operated by Oceanwide Expeditions

Two dive buddies, Evan and his father Jeff Bozanic, joined me from California, a few days before our ship’s departure, and we decided to commemorate the summer solstice by hiking up to an old defunct Coal Mine #2B. We commenced at 23:00 and, crawling up a steep incline over huge boulders, snow fields and gurgling streamlets, reached our destination at midnight, with the sun shining brightly overhead, in an azure sky. At this time of year sun doesn’t set, hence the “midnight sun”. Of course, the opposite is true during the winter where the night is perpetual. However, the locals told me that the lunar light reflects so brightly off pure white snow that it rarely gets truly dark. The town counts more snowmobiles than people.

We boarded the modernized MV Plancius, operated by Oceanwide Expeditions, along with a hundred other passengers for one week of exploration among the many Svalbard islands. Fifteen of us paid extra to scuba dive. Unlike the 20-foot swells we experienced crossing the Drake Passage, from the tip of Argentina to the Antarctic Peninsula, our Arctic foray was like plying the waters of a placid lake.

About the author

Kevin Lee has traveled to all seven continents, and was recently the OCUPS underwater photographer of the year. He resides in Fullerton, California and is an enthusiastic traveler, diver and nudiphile. Kevin's images have been featured in magazines, newspapers, academic literature, and numerous dive related publications. For more of his excellent photography and dive travel stories, please visit his website at http://www.diverkevin.com/.

Further reading

Support the Underwater Photography Guide

Please support the Underwater Photography Guide by purchasing your underwater photography gear through our sister site, Bluewater Photo & Video. Click, or call them at (310) 633-5052 for expert advice!