Satellite Tagging – The SHARC Tag Program

One of the few advantages of lockdown is that underwater camera clubs are getting international speakers to support their virtual meetings. This is a massive benefit and we’ve been fortunate to listen to some very interesting speakers over the past six months. Back in July Peter de Maagt, an accomplished underwater photographer, and antenna specialist for the European Space Agency (ESA) joined the Bristol Underwater Photography Group’s monthly meeting. With a little coercion from our programme secretary Kirsty Andrews he gave a presentation on satellite tagging. He didn’t expect the group would find the subject to be of interest. Sorry Peter, the group loved it.

Most of us are painfully aware of all the wonders of the seas that are being vacuumed up, or choked by litter at alarming rates. Sharks have been very hard hit over the years. I find it difficult to reconcile that sharks attacks make the front page of every major newspaper in the world (there are an average of four fatalities each year). Yet there’s very little press on the 100,000,000 sharks that have their fins cruelly amputated every year, and then, still alive, are thrown back in the water to drown. And all to make bland soup for foreign markets. It’s not fitting for an apex predator who’s evolved over hundreds of millions of years, let alone them being essential to a healthy food chain in our seas and oceans.

I found it soothing that the ESA are sensitive to environmental issues, and in particular marine conservation, albeit there are numerous challenges they need to overcome. Peter presented this information in great detail to us. I will attempt to relay some of those challenges, and their solutions in layman’s detail in this article. All images are supplied by Peter de Maagt, and property of ESA.

Before we delve into the technical aspects of satellite tag development, it’s worth saying that there is an impact from tagging the very animals we’re trying to protect. If animals could speak our language, they’d definitely be telling us that they don’t like having tags attached to them.. Sadly there’s no perfect solution, but hopefully it’s a step in the right direction in order to protect the species and we should take every precaution to do it in the least intrusive way possible.

SHARC stands for Satellite – High Performance – Argos 3/-4 – Receive/Transmit Communication.

After a brief introduction Peter alluded to NGO’s need for supporting technology projects like ESA’s SHARC, and the need for conservation initiatives to be underpinned by real data. There’s often emotive responses to environmental issues, and data makes the issues measurable. With accurate measured data scientists and policy makers can make well founded decisions.

There are a plethora of ways that marine scientists can collect data, and satellite tagging is only one avenue. Marine biologists often want lots of data and that presents challenges for the engineers like Peter who develop the tags. The technology exists to capture a lot of data like depth, temperature, water salinity, light intensity, the x-y-z of animal movement, etc. Capturing all of this data has technical implications. More memory is needed to store the data, and while memory is cheap these days, you need extended battery life to support increased memory. There is always a balancing act to be made : measure a lot of parameters for a short period of time, or fewer parameters for a longer time. Cost is another key factor, and satellite tags are not cheap. These are a just a few of the considerations which need to be addressed as tags are developed.

Most of us were more than a little shocked when Peter asked us how many satellite tags we thought were deployed on sharks between 2002-2017? Most of us thought thousands. The answer is abysmally low at 1,681 tags deployed on only 23 species as can be found in scientific literature. That’s just over 100 tags per year or 75 tags per species. High costs tend to limit tagging studies to either commercially important, or highly charismatic species like great whites, or tiger sharks, which sadly leaves not very much data for the remaining 19 species.

So in an ideal world we’ve got lots of tags deployed and lots of data collected. Neither of these are easy to do. Peter shared a brief animation with us showing buoys floating in the ocean, a turtle, polar bear, and an albatross each wearing tags, and they satellites they communicate with. Once the tags detach from the animal, they float up to the surface and start sending data up to the satellite, and further to that once the satellite passes a ground station the data is transmitted down to mission control. Thus the cycle is complete. The gist of the animation was to highlight an issue with tags attempting to send data when no satellite was immediately reachable, and the inherent inefficiency of this which was draining the batteries of the tags too quickly. Thankfully the engineers at ESA have provided a solution for this. Rather than the tags trying to send data as soon as they’ve detached from an animal, they only send brief ‘are you there?’ messages until an acknowledgment from the satellite is received, and only then is all the data transmitted to mission control.

Key properties that ESA incorporated into their tags are smaller and lower weight, longer battery life, increased memory, and bi-directional communication with the satellite, and hopefully reduced cost to make the chips used in tags.

Peter explained that initially they didn’t think producing the housing of the tags would be too difficult as the materials they use were the very same used in rockets, and aircraft. Theory is often different from reality though, and Peter shared some of the results of iterations they went through to come up with the finished product. The first attempt at 130 bar of pressure (1885 PSI ~) cracked their initial prototypes failed. Peter went on to explain that many animals are also diving deeper than 130 bar. In light of that they devised a glass cannister that will break at a set pressure, and cut the link to the animal allowing the tag to surface as an additional safety feature.

Peter was fortunate enough to be able to join a group of scientists in the Dutch Antilles to perform studies in the field at a protected area near Saba. It was a relief to hear that although Saba is a very small place, they’ve managed to establish a fairly sizable protected area (see dashed line around Saba on map) where sharks thrive. Peter was amazed at just how many sharks are out there.

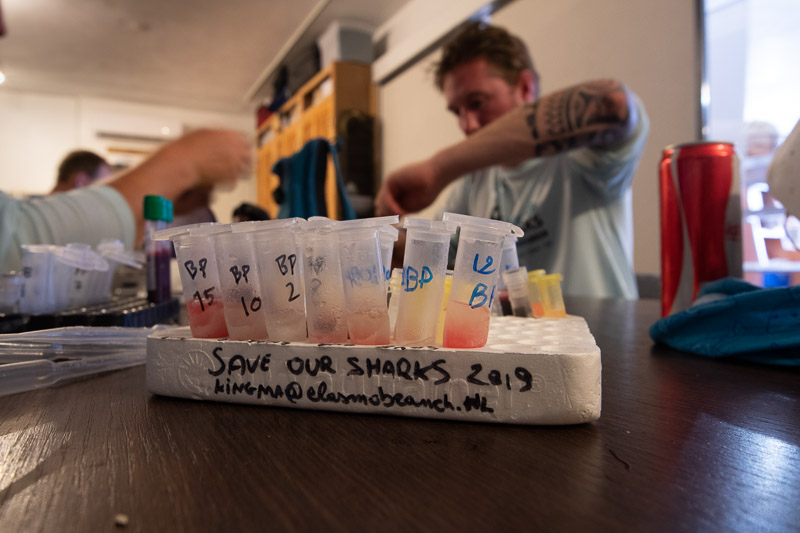

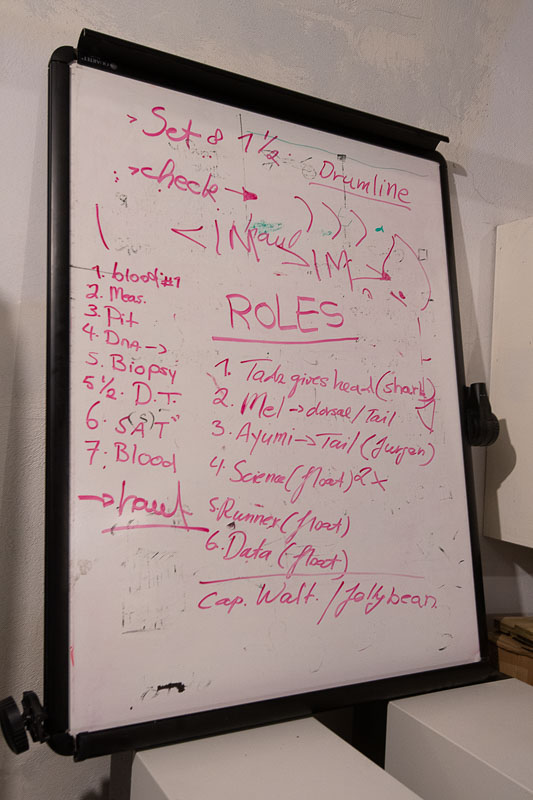

Peter explained that each biologist on the boat had a specific task assigned. Some were simply handling items, while others were taking blood samples, and the usual measurements like sex, length, weight etc. All of this data was recorded and then the satellite tag was attached. This was a very professional group of people and clearly up to the task.

Just prior to departing on the expedition Peter was asked if he wanted to make pictures, This was OK, if a safety diver would be in the water armed with a broomstick! Peter commented that sharks they worked with showed no aggression, but one thing they all shared in common was the need to get away from the boat as quickly as possible. Peter likened them to a torpedo heading down. Being in the water also helped to give visual guidance about the alertness of the sharks after the release. The safety diver didn’t need to use his broomstick … it does say something about sharks don’t you think? Basically they’re not out to get us.

Peter shared an image of data from a tag that was deployed and returned to the surface in the Gulf of Mexico. He commented that this particular trip was helpful for ESA as they collected a lot of useful data for tag development and implement improvements. Peter also mentioned that the computer chip used in the tags is now readily available from a Belgium based company.

The chips that are core in the tags they produce are not just used on sharks, but are also deployed on falcons, seals, turtles, polar bears, and of particular interest is the albatross’. As an example of an innovative project, Peter discussed AIS. All fishing vessels use a system called AIS to identify their location constantly. But sometimes vessels interrupt the signal so they can’t be tracked. This is obviously very difficult to police. An albatross can cover 12,500 miles in about two weeks, they stay at sea for months, and they’re looking for fish, just like fishing vessels. The transceiver they carry can detect radar from more than a five mile radius which boats don’t turn off. So if they encounter fish, they send that data to the satellite. That data can be crossed referenced to see if a fishing vessel was operating illegally in a protected area. This can be useful information to the authorities. Peter loved the idea that albatross are actually helping protect the oceans!!

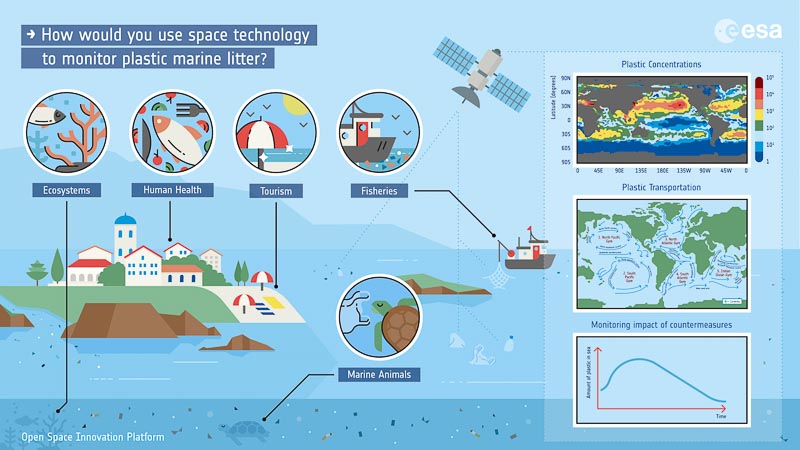

It gets even better as the same chip used in tags attached to animals can be used to help to monitor marine litter.

The strategy here as I understand it to detect the sources of marine litter, and the pathways they take to get into our oceans. And hopefully using models make forecasts on where litter might end up. In the future, and thus help reduce or control it better. The project makes use of trackers that can be attached to marine plastic.

The hope is that the trackers floating among the plastics will provide real data alongside the satellite data and be able to predict where all the plastic ends up, and potentially be able to clean it up.

There are actually multiple projects supported by ESA to address the issues of marine litter which is fantastic to see. Even if some will fail, the ones that succeed will be able to provide very valuable data.

Putting all of this into action is a major challenge for the future, but does leave me with some hope. Thanks to Peter for enlightening us, and being part of the solution.